|

Imagination, Storytelling, |

|

|

Summer Conference |

|

|

|

The Chesterton Review Vol. 31, Nos. 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 2005 LANDSCAPES WITH ANGELS

Including Proceedings of the 2004 Summer Conference in Oxford CONTENTS OF THE ISSUE

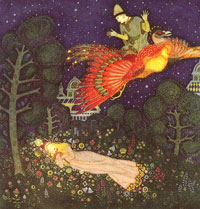

Introduction Draft Introduction to Fantasy Issue "You tell a story because a statement would be inaccurate" – Flannery OíConnor. "I can only answer the question, 'What am I to do?' if I can answer the prior question 'Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?' ... Mythology, in its original sense, is at the heart of things" – Alasdair MacIntyre The question of imagination has become one of the key issues of our time. We are living in a crisis of culture, which is also a crisis of imagination. The old culture of Christendom is passing away. We live among the colliding remnants of many cultures, many civilizations. The question is whether a new civilization can emerge from this jumble, and if so what it might be like. As the great figures of the Christian humanist tradition saw so clearly, every civilization is the product not only of the human imagination but of a religious worldview. Some kind of faith in the transcendent is necessary for people to be inspired to look beyond themselves and form a community that has the power to bind them together and unleash the forces of their creativity. Religious faith gives us hope – hope in the future, hope in each other. If we are prepared to trust in others, and even to die for that hope, then we can achieve greatness. The great founders of religions are therefore also founders of new civilizations. But is a cynical age, an age of doubt and suspicion, capable of giving birth to genuine hope? If not, where are we to find the vision that can inspire us to work together and become more than the mere sum of our parts? Enter the Romantics. In England, Gilbert Chesterton, Dorothy Sayers, J.R.R. Tolkien and the Inklings represent a distinctive response to modernity that draws upon the Newmanian, Coleridgean and even Blakean rediscovery of the importance of the imagination as a means of apprehending religious truth. This was the main theme of the Chesterton Institute conference convened at Christ Church and the Oxford Catholic Chaplaincy in the summer of 2004, on which the present volume is based. It followed in an already-distinguished tradition of Chesterton conferences and special issues devoted to such figures as George MacDonald, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. (It should also be noted that publication of this collection has given us the opportunity to extend the range of contributions well beyond those which were presented in Oxford.) The best known works of the Inklings (and of the wider group of writers studied by the journals Seven and Mythopoeia) were not philosophical in form, but literary, poetic, fictional and even fantastical – fairy tales and detective stories, sometimes even science fiction. In the last couple of centuries, great writers of fantasy have often been trying in scholarly fashion to reclaim, retrieve and preserve an oral cultural heritage that predates the advent of modernity. But this can hardly be disentangled from the attempt to continue and embellish the tradition. Writers such as Hans Christian Anderson and E. Nesbit certainly need no scholarly excuse to become storytellers of the fantastic. Throughout this literature we see the Romantic impulse at work: in reaction to the rise of industry and a civilization dominated by technology, a fascination with fairies and nature-spirits can easily be understood. (The same impulse was present at the birth of the very different genre known as science fiction, which instead of turning its back on technology attempted to romanticize it.) It was widely felt that something important was in danger of being lost, even if no one could agree precisely what that was. In fact the attempt to recapture or remember it became an obsession in the Victorian and Edwardian period. Then came a real watershed for European civilization: the First World War. This has been called the first modern war, and we often forget just how modern it must have seemed. Suddenly there were great lumbering tanks like monsters in the smoke, and death raining down from silver zeppelins that appeared like something dreamed up by H.G. Wells. A book by John Garth, Tolkien and the Great War, has emphasized the extent to which the soldiers in the trenches found refuge and solace in works of medieval and Victorian fantasy: the Arthurian stories, E.R. Edison, Lord Dunsany, William Morris. In order to express their experiences, many of these fighting men turned to writing either fantasy or poetry themselves (Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfrid Owen, Robert Graves). It was in these circumstances that one soldier, J.R.R. Tolkien, began to produce the great legendarium that lies behind his later novel The Lord of the Rings. In it he tried to define and preserve the elements that are necessary to build and defend a civilization: a pattern of heroism, a sense of meaning and overarching providence, a belief in vocation, and a love for the natural world. Tolkien wanted to sound a trumpet-blast to awaken the hobbits of England to their most urgent task: the scouring of the Shires and Counties, the towns and villages, from the blight of what Chesterton called "standardization to a low standard." But it was too late. Much that once was has passed away, and no one is left to remember it. "People are inundated, blinded, deafened, and mentally paralyzed by a flood of vulgar and tasteless externals, leaving them no time for leisure, thought, or creation from within themselves" (G. K. Chesterton, speaking in Toronto in 1930). Our contributors regard the truths embodied in Tolkien's mythology, and in other fantasy works of a similar type produced within the wider tradition of fantasy, as in some way perennially valid; they contain truths that like seeds can sprout in unexpected places and times. We explore in this volume how it is that a fantasy can both contain a search for truth and embody the truth itself. In order to do that, we will need to reflect on the nature of the human imagination itself, and its relation to the truth of the world. Readers will naturally differ in which fantasy stories, and which writers, they find most appealing or interesting. We invited speakers to our conference who we felt would share at least some appreciation for the Inklings in particular. In the modern context, where other fantasy writers, notably Philip Pullman, make a virtue of opposing the "Christian-Romantic" assumptions of Lewis and Tolkien, this might open us to the charge of bias, and I freely admit that we have chosen sides. But we have done so for a reason, and that is because we are ourselves Christian-Romantics. Our Institute's patron, G.K. Chesterton, was situated in the same tradition. Why "Landscapes with Angels"? The word "Angel" (Gk. aggelos) originally meant "Messenger," and the Angels are messengers of the Most High, messengers of Light, messengers of the transcendent. Not only do they appear in the kinds of stories we are discussing here, but they also may influence the writing of them, and the best stories become messengers in their own right, in which something of heaven gleams through. We all need such messengers, from time to time. Certainly children's hearts, which are so ready to awaken, will respond to the call of the messenger when it sounds. [I.B. and S.C.]

|