The Sky at Night 8 March, 2007

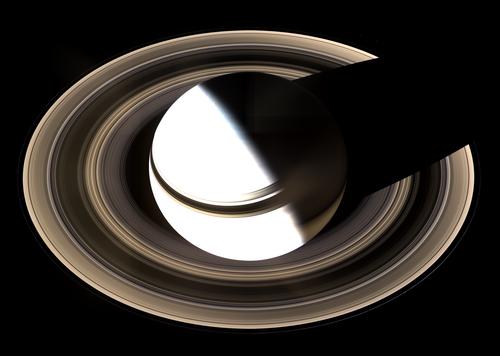

This is what science is about, what makes it worthwhile – the discovery of beauty. This wonderful picture of Saturn from the Cassini space-probe, and the glorious vistas of deep space opened up by the Hubble telescope, are the kind of thing that get people interested in science as a career. Not to mention the unsolved puzzles. Why does one of Saturn’s moons look as though its two halves had been stuck together with glue? Why is another, a tiny ball of ice, venting like a volcano to create the E-ring? In Britain the long-running television programme ‘The Sky at Night’ is about to celebrate its 50th anniversary. We congratulate and thank Sir Patrick Moore for all that he has done to awaken minds both young and old to the splendours and curiosities of space.

We know that the great breakthroughs of science are made with the aid of imagination; they involve creation as well as discovery. This suggests that the gulf between science and art can be bridged, but probably only if we give up the modern notion that beauty is merely subjective, existing not in the world but only in our minds (as if our minds were not also part of the world!)…

The purpose of art is surely not just to shock, to amaze, to entertain, or even to transform our perception, but to do all these things by revealing something to do with reality, to reveal something TRUE. Thus the gap can be bridged in both directions.

What then is the difference between science and art? Maybe art is searching for beauty and truth in the way things appear to us, even if it uses appearances to speak of something deeper. Science, on the other hand, searches for beauty and truth behind appearances, in the hidden order of causality.

The medieval concept of a ‘liberal arts’ education is interesting: grammar, logic and rhetoric (needed for communication and argument) were followed by the study of arithmetic, music, geometry and astronomy – not all of them ‘arts’ in the modern sense, but at that time the split that defines our culture had not yet taken place. The four disciplines of the quadrivium had at least one thing in common: a basis in number, in mathematics. Music was the expression of numerical harmonies in time, geometry the exploration of relationships in space, and so on. The assumption here was that by learning to understand these relationships, this harmony in the cosmos, our minds would be raised towards God, in whom we could find the unity from which they all derive, the ‘love that moves the sun and the other stars.’ Thus the quadrivium would prepare the ground in us for the contemplative sciences, philosophy and theology.

Perhaps we need to think in fresh ways about education in our time. Perhaps we need to rediscover the liberal arts.